SUSTAINABILITY

e for emancipated

According to the German engineering journal Ingenieurblatt, 60 percent of waste in Germany in 2022 was attributable to building materials, and the Climate Economy Foundation estimates the construction industry's share of total waste generation to be very similar at 60 percent. From a self-protection perspective alone, it is therefore important for humanity to significantly reduce this share so that not only are significantly fewer resources consumed, but the materials used can actually be reused in the event of conversion or demolition. In order to meet the legally binding climate targets to which the Federal Republic of Germany has committed itself, it is therefore necessary to change the way in which planning and construction are still carried out in far too many areas.

The combination of around 3,000 standards and concerns about liability consequences has also often led to the recognized rules of technology being overfulfilled in Germany. Under the prevailing legal and liability situation, a building was only considered “defect-free” if the recognized rules of technology were exceeded by the architectural and engineering firms and if the highest possible standard was chosen for comfort and equipment features. To protect against subsequent liability claims, a planning and construction process developed within a normative framework that far too often exceeded the actual needs of the users. Meticulously detailed sound insulation requirements, oversized technology, or simply too many power outlets increased costs and hindered innovative and simple solutions.

The regulations brake

One solution is the so-called “building type e.” How the ‘e’ is interpreted is a matter of opinion and interpretation. For some, it stands for “easy,” for others, “experimental.” The fact that the so-called “building type e” became an issue in the first place is due to an initiative by the Bavarian Chamber of Architects. Against this backdrop and at the instigation of the Chamber of Architects, 19 pilot projects were launched in Bavaria to show that there is another way – each accompanied scientifically by a research group led by Professor Elisabeth Endres. She heads the Hausladen engineering office in Munich alongside two managing directors and another member of the management team. Since 2019, she has also been teaching and researching as a professor of building technology at the Technical University of Braunschweig. The Bavarian pilot projects cover a wide range of areas, from school construction to existing building and neighborhood development to residential buildings.

At the beginning of December, Federal Minister of Construction Verena Hubertz (SPD) stated in a LinkedIn post: “In Germany, construction is being slowed down in many places by too many regulations. At the same time, costs continue to rise. That is why new steps are needed.” Together with Federal Minister of Justice Stefanie Hubig (SPD), she presented a key issues paper on building type e, which makes it clear that planning and construction in Germany should be “easier, faster, and more cost-effective.” “We are focusing on the essentials, relying on robust materials and compact floor plans, and doing away with superfluous standards that unnecessarily increase the cost of construction projects,” said the Federal Minister of Construction. While architects have been calling for real-world laboratories – and thus legal freedoms in addition to physical spaces – for some time, the current government is now also anchoring “building type e” in civil law in the German Civil Code: “The core element is the new Building Type E contract, which provides legal certainty for deviating from certain recognized rules of technology without this automatically being considered a defect.” The project was initiated by the much-maligned traffic light coalition government and, within it, the Federal Ministry for Housing, Urban Development, and Construction headed by Klara Geywitz (SPD).

Alexander Poetzsch, president of the Association of German Architects, also has some hopes: "Building type e offers many opportunities to advance the construction revolution. Simplified options for converting existing buildings prevent gray energy—or, as I would say, golden energy—from being lost through demolition. Activating existing buildings can save time and resources, revitalize city centers and rural areas, and reduce vacancy rates. Simplification reduces conversion costs, making many projects possible in the first place. Building type e, even in new construction, has the potential to achieve the construction goals that are currently desired by politicians across the board and at a rapid pace – and in a sustainable manner.“ Verena Hubertz also points out the fundamental necessity that makes the initiative so urgent: ”If we want to create more affordable housing, we have to build differently. Building type e offers precisely this opportunity, which is why we want to enshrine it in law in the coming year."

Houses (almost) without heating

One of the first buildings of its kind in Bavaria has now been completed, and the first residents moved in in November: in Ingolstadt, the architectural firm nbundm* has built a “house with almost no heating” for the Ingolstadt Non-Profit Housing Association (GWG). As part of a concept tender, the client and architectural firm jointly applied to the city for the planning of the property on Steigerwaldstraße on the western edge of Ingolstadt. This is where the city literally ends, with the new building located directly on the edge of a field. Regardless of a name like “Building Type E,” according to Chris Neuburger, the building's architect, GWG has long been operating according to precisely those principles that are now labeled “Building Type E.” Standards and regulations have always been critically questioned here, and planners have been given an in-house catalog of requirements that is at the lowest possible level, always with the aim of minimizing construction costs and thus providing affordable and livable housing. And so, in the case of the “house with almost no heating,” the eligibility criteria for social housing were initially taken just as seriously as the locally applicable parking space ratio. As a result, it was possible to dispense with the construction of an underground car park and use around €1,000,000 in construction costs, which would otherwise have disappeared underground – and provoked compliance with further standards – for other things. Neuburger says with a smile: “If you always do your job by the book, you'll run into regulations.” But when you encounter builders who are willing to think outside the box, who are willing to realize different forms and layouts of housing and at the same time take advantage of subsidy programs, “the end result is a building that doesn't invoke so many DIN standards.”

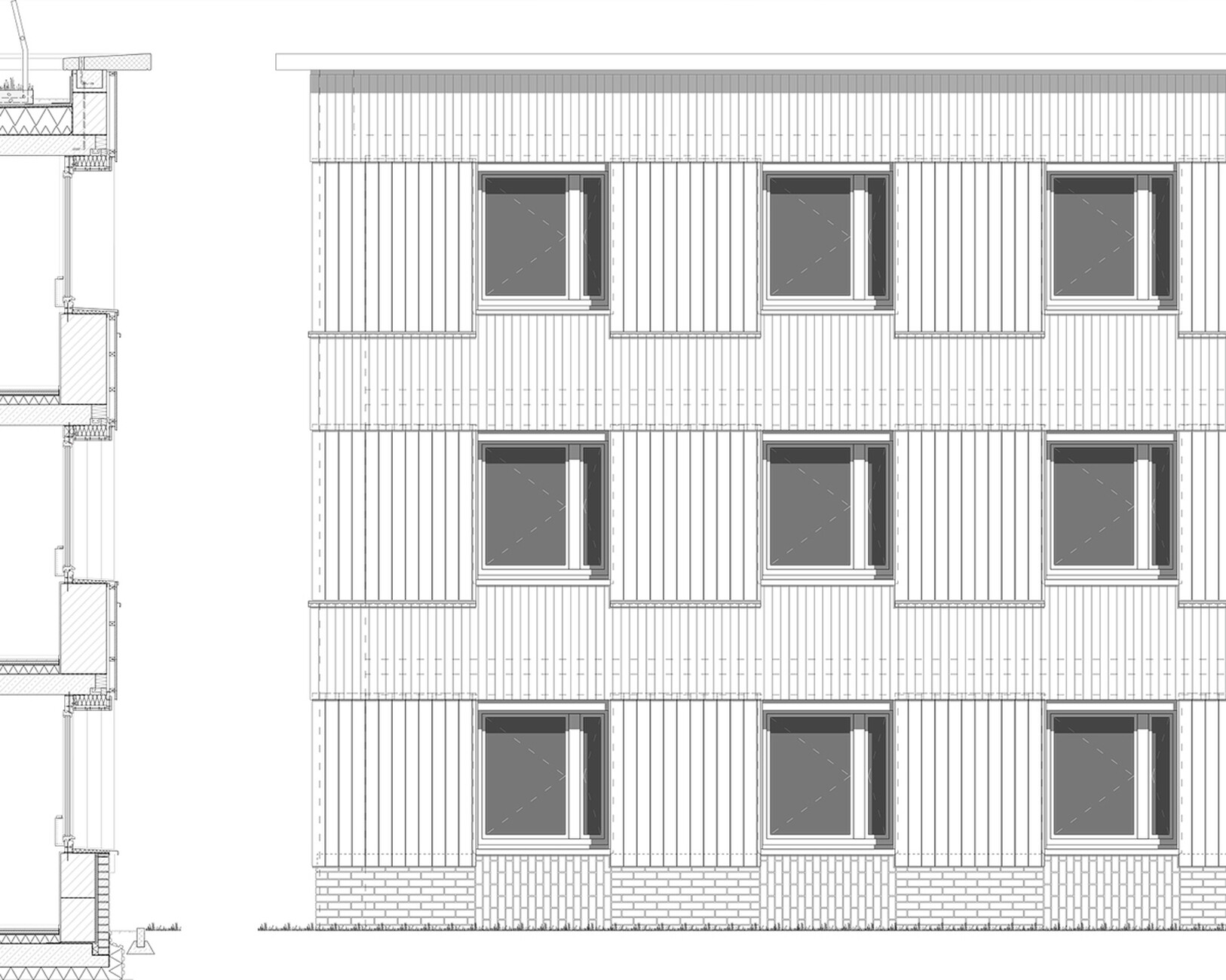

The outcome is a residential building that is actually quite conventionally constructed, stone upon stone with monolithic masonry, clad on the outside with green-glazed boards. Office 2226 from Vorarlberg, a spin-off from BE, which in turn emerged from the Baumschlager Eberle office, ran simulations for months, harmonized a 3D model of the building on the computer with the weather in Ingolstadt, and presented in a comprehensive calculation that the building would be warm enough through use alone and even without heating, as the normal amount of household appliances and the residents themselves generate sufficient heat. “The residents warm up the architecture, which is a beautiful, poetic image,” says Chris Neuburger. As the name of the building suggests, there is an emergency heating system: a thin “heating paper” is embedded in the floors. “Simply to bring the rooms up to operating temperature,” as Neuburger explains. “The residents moved in on a freezing cold November day. So it was important to be able to heat the building up. Some people may want the bathroom to be warmer than others in winter, and we can now achieve that freedom.” Paradoxically, the building had to be exempted from the Building Energy Act, and an energy consultant had to issue the relevant certificates. All this questioning creates additional work, Neuburger admits, but he also says with a laugh: “But it opens other doors for the planners. And when you walk through that door, you suddenly find yourself a little bit in the Shire and not so much in Mordor.” The rooms in the apartments are remarkably large, and the planners did not have to “worry about all the technology,” as Chris Neuburger notes: “For us, the ‘e’ stands for emancipated.” And so he concludes: “The ‘building type e’ gives builders breathing space and planners room for maneuver.” A promising constellation, he believes.

Successful examples here, skepticism there

Alexander Poetzsch also sums it up: "There are already many successful examples, even without the amendment. In the field of construction, especially the renovation of listed buildings, the exception is the rule. There, one can see how it is possible to deviate from the norm in a justified manner. Now it is a matter of transferring this to non-listed buildings, new construction, and, above all, residential construction. I would like all my colleagues to see building type e as an opportunity to look beyond the norm and set new standards."

For the planning industry, it is therefore important to clarify explicitly that these regulations apply not only to building construction contracts, but also to contracts with architects and engineers. A key feature of the draft regulation is the exclusion of consumer protection: the provisions of the Building Type e Act do not apply to consumers or non-expert entrepreneurs. The legislator thus assumes that builders, as expert parties, can assess and take responsibility for the implications of foregoing certain comfort features. An architect who prefers not to have her name published remains skeptical: “I am concerned that this will be used and exploited by the wrong people. In the end, no one will release us from joint and several liability.” After all, she says, the status quo is “far too convenient for everyone else.”

However, if the draft – also based on findings from Bavaria – actually becomes law next year, the new design freedoms would allow for a broader focus on sufficiency, i.e., building only what is actually needed. Instead of maximum technical standards, pragmatic and local solutions, such as the use of timber framing, rammed lime, or hemp fibers, which are being tested in pilot projects, could be put into practice with legal certainty. This would enable the transformation to circular construction to be completed. Building type e creates the planning conditions for this by promoting system separation. Planners could also implement the decoupling of structural and technical systems as an integral part of the design. Such system separation is crucial for the subsequent easy dismantling, classification, and reuse of components. “Much of this is already possible today,” says Neuburger, “but with ‘Building Type E,’ example buildings are being created that could serve as models for many more builders.”