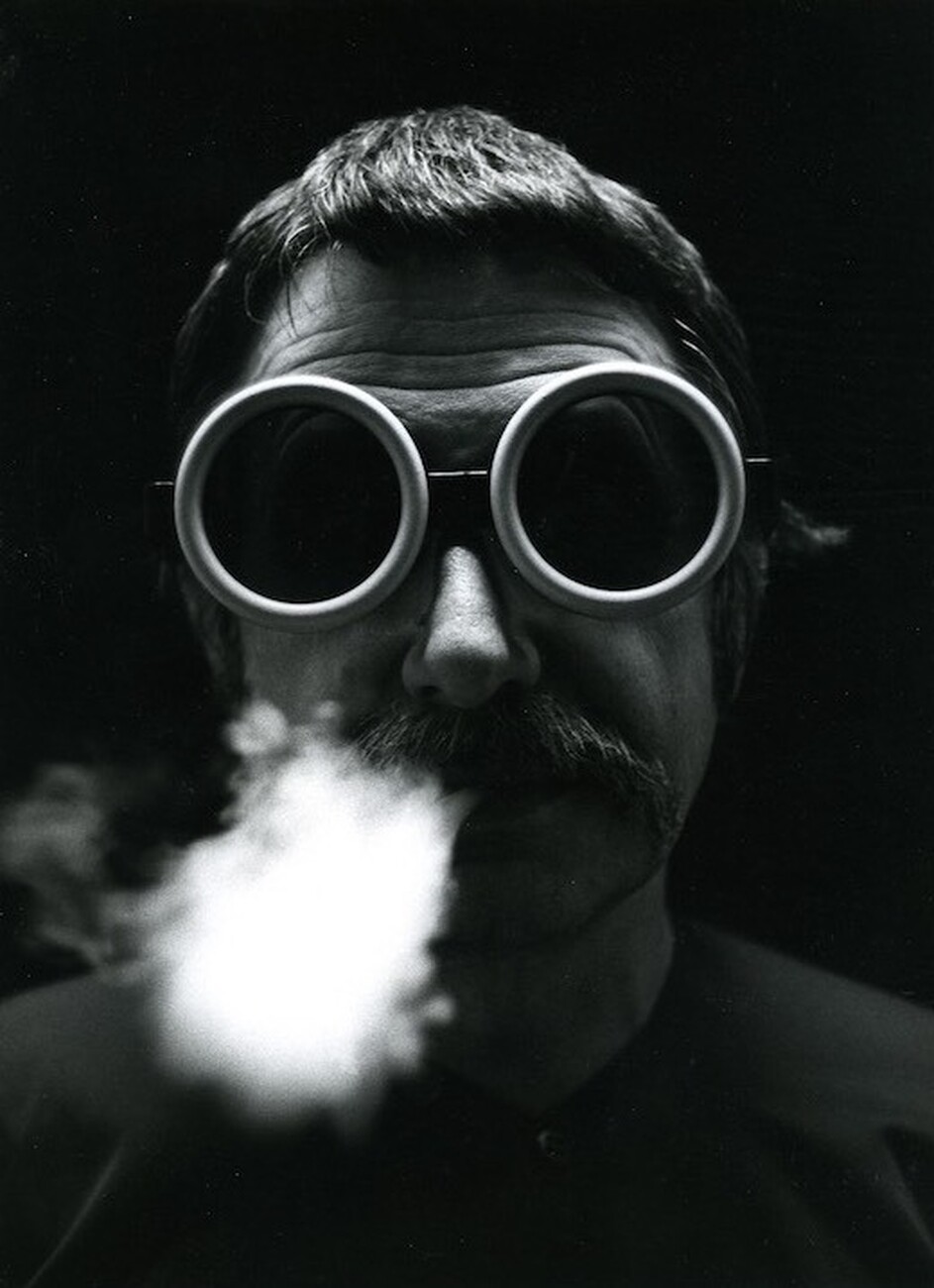

What are they doing in there?

When hearing the name Ettore Sottsass – and especially so today, on the day he would have turned 100 – many believe that they know what he did, what he created and how he thought. Not who he was as a person: Only his family and friends would be able to say that when remembering him. But what he wanted as a designer and architect, what he actually achieved, which exceptional objects he designed. Names and buzzwords are quickly cited: Memphis certainly, furniture – tall wardrobes with plastic laminate in colorful stripes, with their striking appearance still calling into question everything we are used to even today – some might also refer to radical and anti-design. Or they may mention Olivetti, an entire working world on the cusp of becoming a “business machine,” or movable, modular furnishing systems, architectural structures for faraway planets, colorful glass objects.

Yet all of these objects and ideas still give us the impression of being strange, like spirits sustained by a myth we do not know, or totem objects of a hectic civilization that constantly aims to understand itself through its products, in the conversation between humans, humans and nature, humans and technology. Or could all this be nothing more than design history – frozen in plastic, wood, marble, glass and metal?

Those who would like to find out more about how Ettore Sottsass perceived and felt about the world around him (and of course his 100th birthday is as good a reason as any for doing so) should read his travel memoirs. In the early 1990s they were shown under the title “Adesso però” at Deichtorhallen in Hamburg in the context of an exhibition and have now been published in German.

Traveling to faraway countries, to India, Nepal, Burma, but also to the United States, to New York or San Francisco, meant opening himself up to people and to the world. Sottsass himself said that through traveling we were able to find “a new point of reference for our thoughts, our gestures, our feelings,” to renew ourselves. Maybe, he wrote, we would also “become more patient with all of those we live with” after a beautiful journey. Traveling confuses us, corrects us and relativizes our own actions and point of view; it adjusts meanings we have rehearsed over time.

And so, when in 1962 Sottsass and Nanda Vigo were stranded at Calcutta Airport on their way to Rangoon and a helpful Indian policeman expressed his desire for quite a particular present from Italy – a fountain pen – Sottsass wrote: “Italy became small, distant, superfluous and pointless, and it became crystal clear that what were celebrated nationally as deeds of glory had but a small private sphere of influence, just like mother’s delicious cake.” The focus had shifted: What one had previously thought of as the center of one’s life – and indeed the entire world – was suddenly moved to the margins, was only half as important.

In India in 1962 Sottsass was interested in the philosophy of love, the colors and the small gestures. He found it hard to understand that there was “too much tension,” there, “too much vitality, too much freedom, too much dominance of a non-Cartesian space, too much sway of an irrational space.” And when traveling through North America in 1966, he jotted down his thoughts on apartments on the West Coast under the heading “What are they doing in there?”: “The apartments of friends of friends on the West Coast, as they say, are nothing but shells. That will later be disposed of. The apartment is nothing but “packaging” for the gestures of everyday life – an idea that may well work, despite the word packaging being so fraught with commercial meanings and those to do with money that it becomes troubling to use. Yet all American life plays out and circulates on the basis of this concept of packaging. Packaging means to wrap something, the process of making a parcel, and this in turn means shrouding something. In general, the contents are the most important part of the parcel, and the wrapping tends to be thrown away. Life is important. The gestures of everyday life. The gestures without myth, the gestures that become used up one after the other in themselves, that arise one out of the other in a process of almost uncontrollable proliferation, all of this is important.”

A journey of a very different kind began three years later, when Sottsass switched on a “color TV with the wrong buttons” in a hotel in Manhattan and Sophia Loren appeared, “her beautiful face covered in purple stripes in the hue of cyclamen, those that grow wild, that you used to find in shady forests and that no longer exist nowadays, and the sky behind Loren was a little green, like good jade, apple-colored you could say, and a little pink, like the color of blue daisies...” This fascinated him and made him start thinking about a filmed life “detached from the conditions of the planet, detached from history, i.e., from time and space-time relations, such as exist down here on the planet.”

A great deal changes, even travel. And so he noted in 1992 in his travel memos “On kitchens”: “The new rituals slide across the photographed labels ... We travel continuously in a slow, perpetual rain of beautiful labels, in a rain so heavy and thick that we are unable to see through all of these labels, see what may be beyond them; rather, we don’t want to see everything that might possibly be beyond them, because we are very happy with what is here … The censorship of things that do not work grows, the wall of labels grows.” Ettore Sottsass always sought to look beyond the wall.