IMM COLOGNE 2018

Sitting in a flower

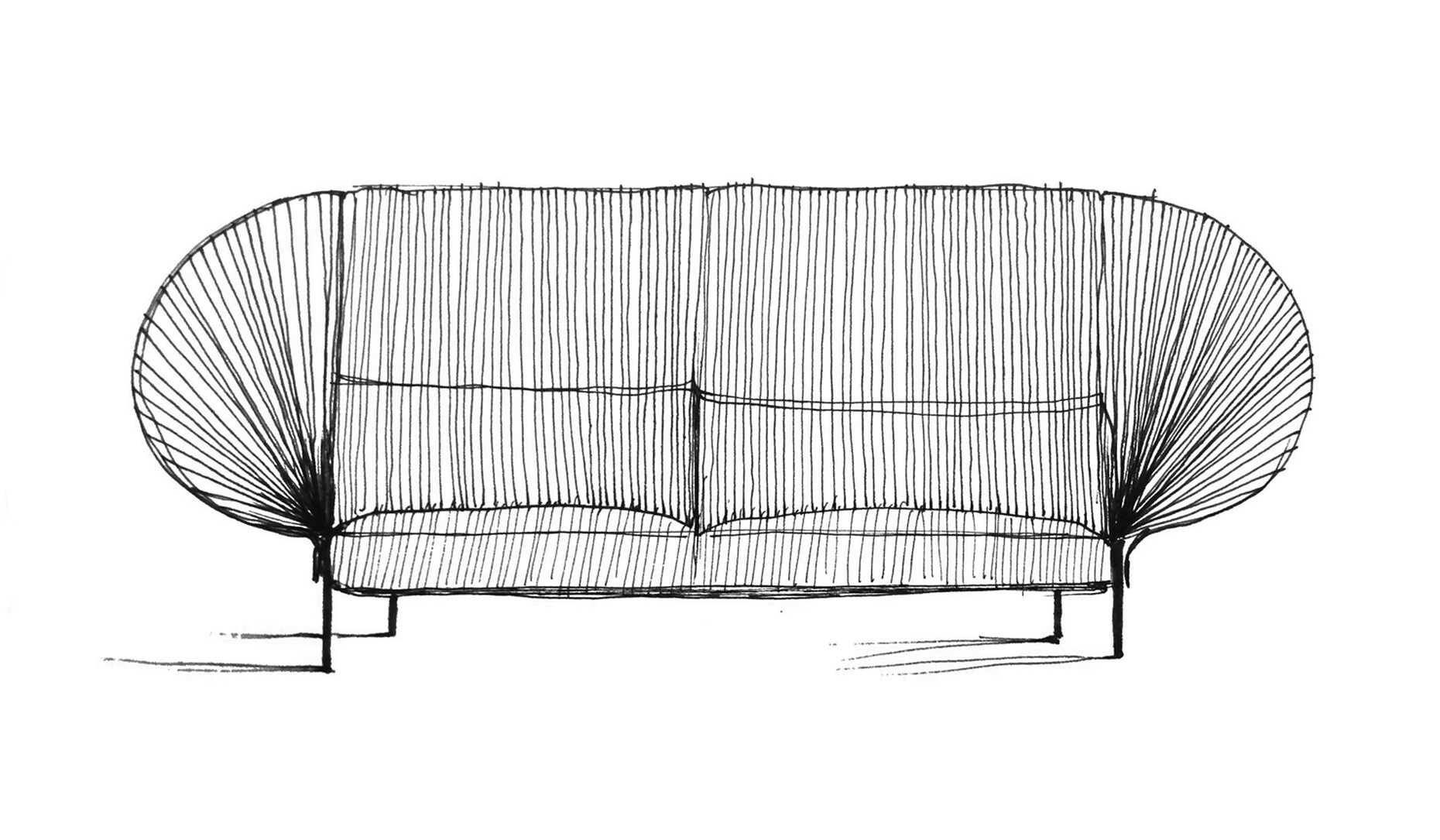

Thomas Edelmann: “Paipaï” combines a technological approach with a very thin and elegant structure, as well as organic and expansive shapes. What is the idea behind the project?

Paolo Lucidi: The collection consists of a three-seater sofa and a loveseat with space for more than one person. It is a cross between an armchair and a sofa. “Paipaï’s” armrest is more than a standard side support or boundary. It provides a certain amount of resistance, so you can also sit on it; on top of that it is soft, flexible and comfortable. Its shape is inspired by origami techniques – or to be more precise, by traditional Japanese fans. Their flexibility and stability is also based on folding. To begin with, our design included an armrest structured by a series of incisions.

Luca Pevere: Later on we decided to strongly reduce this structure.

How did the form change throughout the design process?

Paolo Lucidi: After seeing the first prototype in Briord with Ligne Roset we simplified the shape. We found that in this way the piece would be easier to produce and understand, too. It gives it a more iconic look and feel. The folded armrest is fixed to the side of the frame with two visible screws.

Luca Pevere: “Paipaï” invites you to be seated in a somewhat informal way. If you like you can even sit or lie on it diagonally. The screws used to attach the armrests to the rest of the structure might be somewhat reminiscent of French design traditions, such as the work by Jean Prouvé, who made his constructions apparent. The screw connects everything...

A screw holding the world together?

Luca Pevere: Yes, it constitutes the connection to the minimalist tubular-steel frame. It links the upholstered seat and the wing-like armrests. Flat paper that hasn’t been folded is fragile. Folding it lends it stability.

Folding paper to create a one-off, as one would do in origami, seems comparatively easy. But it is different when the material to be folded is upholstery foam or fabric rather than paper, and when you are folding the material to create a serial product. How did you get to grips with that?

Luca Pevere: You would need to ask the suppliers for an extensive answer to that question. But essentially you squeeze the foam, which creates an indentation in the armrest that simultaneously generates the three-dimensional structure.

Paolo Lucidi: As Italian designers we have recently seen a lot of sofas based on the modular stringing together of flat boxes. These sofas are all very similar. We wanted to counter this with a more international proposition. At the same time “Paipaï” is an object that can be placed in the center of a room, as it has an effect from all sides.

Luca Pevere: It has a strong character, a pleasant vibe and yet gives off a serene impression. That’s what we wanted to achieve, and it was another reason for reducing and simplifying the original multiple armrest folds.

Paolo Lucidi: Nowadays a low backrest is regarded a badge of contemporary design. But in this case, we wanted to create something extraordinarily comfortable. You see it at first glance, and as soon as you sit down you feel it, too. The high backrest supports your head.

You founded your joint studio in 2006. In the 12 years since, the world as a whole – but also design – has become increasingly faster paced and dynamic. People are trying to live a digital life to an ever greater extent. Furniture on the other hand is tied to the analog world. What does this tension mean for your work?

Luca Pevere: We are very much connected to the analog world because we like to work with a range of different materials. That includes everything from the concrete lamp “Aplomb” for Foscarini to the “Alburni” tables for Ligne Roset, which use an ultra-thin, crosscut veneer. The digital era is speeding up. At the Stylepark presentation held at the MAKK we found out that the platform’s software is being changed to enable users to access images and content faster. Yes, this ubiquitous acceleration does exist. Yet our work is still focused on our main aim: creating durable products. Sometimes it’s strange to watch things changing so rapidly. But we try to hold on to physicality through our approach.

Paolo Lucidi: There isn’t just one way of doing design. Some of our fellow designers take a very active part in the acceleration by creating a lot of products in a short space of time. We like to take time for a new design. Sometimes you also need to take a break for a while, in order to come back later and reassess whether an idea is good or not. And so we will work on a new product for anything between one and three years. The things we create are not fashion. We design for a market that appreciates longevity.

Luca Pevere: Of course the digital world influences us, too. We see objects devised that employ new techniques all the time. For us, new technologies already play a role as new design tools. But they aren’t used to create furniture items or furnishings. Why would you want to have a table with six chairs 3D-printed?

The philosopher Zygmunt Bauman describes our current world as a “retrotopia”, as shaped by backward-looking fantasies. We only feel safe in a scenario of objects and ideas conjured up from yesteryear. Design, too, seems rather reactionary nowadays. You on the other hand aim to live up to the traditional notion of design: that of searching for the new and aiming to change things. Does this approach still work? How do you discover the ‘new’?

Paolo Lucidi: Being able to create an aspect that reminds people of the past doesn’t necessarily have to be a bad thing. It is easier to understand a new product when it has a detail, a material or another connecting factor that links it to something we are familiar with. But at the same time you should aim to create something new. You need to find a balance.

Luca Pevere: We come from a region where our parents and grandparents repaired and adapted things. They felt very connected to the objects they surrounded themselves with. They would have never thought of replacing them in their entirety after just a short while. Maybe we should aim to combine this mentality with the one we have now. At the same time, we designers are a tool of sorts for the companies we work with. Good designers ought to understand the company they are working for. They should know its portfolio, its catalog, and its traditions. This way, you can go a step further, but you are still taking the past into consideration. This connection is vital. It’s impossible to create something entirely new.

You have worked with many important companies. Ligne Roset is known for its creative understanding of design that is at the same time based on commercial success. What do you consider to be the characteristics of this collaboration?

Luca Pevere: Our first project for Ligne Roset was the “Alburni” table mentioned earlier. We weren’t entirely satisfied with this though, because the company is famous for its sofas. We were later able to join forces in the way we had hoped with “Backpack” and now with “Paipaï”. They invited us to Briord for the production, where we got to know the depth of skill this company has at its command: They know how to treat upholstery foam and seams, how to use textiles – they have a warehouse with 4,000 different fabrics – and that’s really great and corresponds with what we wanted to achieve in our collaboration with the company. We wanted to get to know its core business, its most important field of expression, and contribute to that. We like the French spirit and the company’s search for iconic designs. That’s why we aimed to continue the line of tradition that gave rise to products such as “Togo”, “Ploum”, and “Confluences”. All of that is far away from the world of Brianza, which we know in Italy.

Paolo Lucidi: We hold the family that runs the company and the people we worked with there in very high esteem. It is not our goal to collect as many brands as possible. We just want to work for a few of them. In general we choose the brands we work with according to the people who work for them. The people who work at Ligne Roset are friendly and know what they’re doing – that’s not a given.

You both studied in Milan at the renowned Politechnico di Milano. As young professionals you decided to move to the Udine area, the border region of Italy, Slovenia and Austria. Why is it important to you to live and work in this region in particular?

Luca Pevere: Well, for one thing, we’re from that region. We lived in Milan for eleven years. Maybe it was something like a call back to our origins...

Paolo Lucidi: ...to our roots...

Luca Pevere: Of course we love the region, the space you have there and the green environment. But it is also important to us to be a little isolated during the design process. It is good not to have any contact to the outside world for a while. During that time you develop something and assess it. Then you present your ideas and see how other designers and the rest of the world react to them.

Paolo Lucidi: We have traveled a lot in recent years. Without that, living in such a rural area might be a bit too isolated and boring in the long term. We are often in Milan and Paris. But we need a quiet space, both for our work and to unwind. Another strategic reason for living there is that there are a number of districts in the area with firms specializing in particular materials, such as wood and fabrics. And companies like Moroso are based there, too. There are no magazines or journalists there, only industrial suppliers. That’s very helpful.

Paolo Lucidi (1974) and Luca Pevere (1977) studied in Milan. They began working together in 2003; in 2006 they founded Studio LucidiPevere. Their work is centered on unusual techniques and materials, aesthetic meaning and new types of products.