Ornamental brickwork

Whether it's her double mosque in Amsterdam or her sports hall in Groningen, hardly anyone has such a keen sense for brick as Marlies Rohmer from Amsterdam. Most recently, the architect completed the Maggie's Centre in Groningen, which is located right next to the university hospital's new radiation centre and offers a place for counselling, communication and healing for cancer patients and their families.

Robert Uhde: Ms Rohmer, one of your most recent projects is Maggie's Centre in Groningen, which opened in 2024 and features wonderfully light architecture made of clinker, wood and concrete. Surely a very moving project, right?

Marlies Rohmer: Yes, it is indeed a very special project. The first Maggie's Cancer Support Centre was opened in Edinburgh in 1996 – initiated by Maggie Keswick Jencks and her husband Charles Jencks. After Maggie was diagnosed with breast cancer, they both experienced first-hand how stressful the atmosphere in medical facilities can be. Together, they founded an initiative that offers free, professional support to people diagnosed with cancer and their families – in an environment that is not only functional but also architecturally unique. Charles Jencks, himself a well-known architectural theorist, used his network to win over renowned architectural firms to the idea. Today, there are 27 Maggie's Centres worldwide, most of them in England and Scotland – designed by Frank Gehry, OMA and Norman Foster, among others.

The Maggie's Centre in Groningen is one of the first three of its kind outside the United Kingdom. How did the commission come about and how did you approach this special construction project?

Marlies Rohmer: I was very moved to be invited to participate in the competition for the project along with two other firms. After the competition was announced, I travelled to England and Scotland to visit various Maggie's Centres and talk to the people there: what works well, what doesn't? Based on this, I further developed my concept and refined it with the specific location in mind.

The project gave you the opportunity to consider the architecture, interior design and landscape together from the outset.

Marlies Rohmer: Maggie's Centre is located on the northern edge of the University Medical Centre Groningen (UMC) campus, right next to a busy intersection. To create a place of tranquillity despite this, we worked with landscape architect Piet Oudolf to embed the building in a small garden. The result is a building with two faces: to the north, the building opens up with floor-to-ceiling glass surfaces onto a densely planted terrace and a newly created watercourse. To the south, east and west, large French doors connect the interior rooms with the garden. Inside, we have created an airy interplay of rooms of different sizes – with varying degrees of privacy and an open double-storey kitchen as a central meeting place. Plenty of daylight, light-coloured materials and warm surfaces create a friendly, inviting atmosphere. And curtains allow the character of individual rooms to be flexibly adapted, for example for counselling sessions, self-help groups, yoga, painting or cooking classes.

Another special feature of the building is the unusual façade design made of precast concrete elements with clinker bricks of varying sizes incorporated into them. It is striking that you often work with brick. What significance does this material have for you?

Marlies Rohmer: Clinker is an incredibly versatile material – and one that ages beautifully. A single brick often looks inconspicuous, but when used in large areas, it begins to speak. And the beauty of it is that you can use clinker to speak many different languages. For Maggie's Centre, I worked with precast concrete elements into which clinker bricks of different sizes and colours were embedded in a special pattern. In addition to a more orange-coloured Groningen clinker, we used a dark brown brick to create a connection to the Oosterkerk opposite, a characteristic brick building of the Amsterdam School. At the same time, there are many buildings with concrete façades on the UMC Groningen clinic grounds – so I found it exciting not to cover all surfaces with clinker, but to leave the concrete visible. The result is a play on the materials and building typologies of the surrounding area.

Your work is characterised by rich, often ornamental façade design. In the Netherlands, ornamentation was frowned upon for a long time – despite the great tradition of the Amsterdam School. Why did you decide to break this taboo?

Marlies Rohmer: I studied at Delft University of Technology in the 1980s, and at that time ornamentation was indeed absolutely taboo there. Nevertheless, I attended various seminars on masonry construction because, in addition to design, I was also interested in the craftsmanship and technical aspects. I was particularly inspired by the work of Frank Lloyd Wright – especially his Ennis House in Los Angeles. The building appears to be cast from a single mould, but has a powerful ornamental structure on its surface. The situation is similar in Hamburg's Speicherstadt. Here, too, the ornament ages along with the material, giving the buildings patina and depth.

A good example of this approach is the double mosque in Amsterdam, which opened in 2008. The building houses prayer rooms for the Moroccan-Islamic and Turkish-Islamic communities and also incorporates an urban social centre...

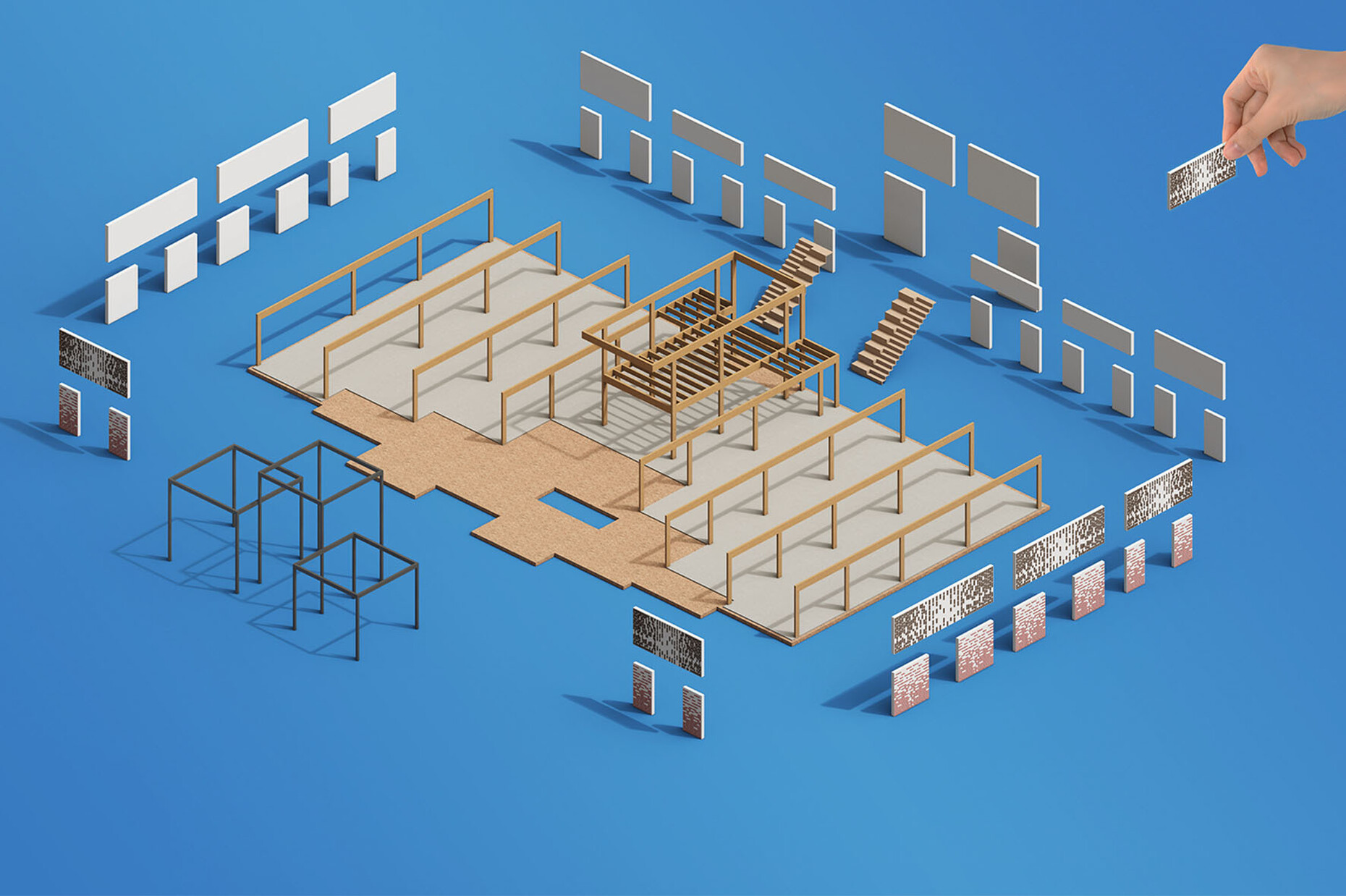

Marlies Rohmer: With this project, I deliberately wanted to avoid creating ‘homesick architecture’ and instead design something that blends into its surroundings while also giving local people a sense of identification and pride. That's why I chose brick as a typical Dutch building material, but used Turkish and Moroccan architectural elements in the façade design. The result is a kind of cultural hybrid: a lively collage of different brickwork patterns and a wide range of colour nuances in the selected hand-moulded facing bricks – from light yellow to orange and dark red to grey and black. Unlike at Maggie's Centre, we had all the ornamentation done by hand in the traditional way because we had a very good bricklayer. But even back then, we had already thought about using prefabricated elements made of clinker and concrete for the façade, similar to Maggie's Centre. This now offers many advantages. Above all, it makes it much easier to achieve the plasticity that characterises older brick façades. Otherwise, it is now hardly affordable, even if you can find the right bricklayers for the job. In the past, labour was cheap and materials were expensive – today it's the other way around. Prefabricated elements therefore offer great advantages, especially when you want to implement repetitive patterns. What's more, the concrete elements can be easily hung in front of a wooden frame as loose panels and can therefore be easily removed and used elsewhere in line with the cradle-to-cradle concept.

Your double sports hall in Groningen, completed in 2014, also features distinctive clinker brick architecture. The front façade appears to undulate upwards in four increasingly larger steps in a dynamic gesture. How did this design come about?

Marlies Rohmer: It was actually a very complex task: we had to integrate two sports halls, one above the other, into a small row of brick buildings, and at the same time, for functional reasons, the façade had to be almost completely closed. In order to still bring sufficient natural, glare-free light into the interior, I took inspiration from Alvar Aalto's Santa Maria Assunta church in Riola di Vergato. We translated the shed roof structure used there into a vertical design and developed a closed clinker brick façade on the street side, which is staggered upwards in four large waves. The upper three waves are each covered with horizontal glass strips – they act like light traps, providing both sports levels with diffused daylight. The lowest wave, on the other hand, is at seating height and serves as a long bench in the public space. And thanks to the choice of reddish-brown clinker brick slips, the building also blends seamlessly into its surroundings in terms of materials. The façade is particularly impressive in the evening hours, when the artificial light from inside enhances the sculptural effect and the building appears as an interesting light sculpture.

It is exciting to see how the final form gradually develops from the diverse requirements...

Marlies Rohmer: Yes, and I find this search incredibly exciting because it makes every project unique. At the beginning, there are often completely different ideas, but during the process you realise that it doesn't work that way. Then it's time to ‘kill your darlings’ in order to remain open to new approaches and implement certain ideas in an even more subtle way. It's all part of a search process that is not one-dimensional. Many things and perspectives come into play.

In addition, you also build with other materials. For example, your design for the 15-storey student residence in Utrecht (2009) attracted a great deal of attention with its confetti-like façade made of 4,500 pixel-like aluminium panels in different colours. What criteria did you use to select the materials for this project?

Marlies Rohmer: In the run-up to the project, I first took a look at some of the existing halls of residence on campus. I was somewhat surprised to find that some of the façades were already heavily soiled because food was often thrown out of the windows. Accordingly, I wanted to use a material that was less susceptible to this. As a first step, I therefore considered designing the façade with aluminium panels in 25 shades of grey to reflect the character of the surrounding concrete buildings on campus. However, the client wanted more colour. As a result, despite my initial concerns, we implemented a dazzling outer shell with aluminium panels in green, red, orange, black, white and grey, which playfully conveys the coexistence of students from different nations to the outside world. All panels are exactly the same size as the window frames. This allows the elements to visually merge into a lively, almost pixel-like carpet of colour in which the windows almost disappear. The deep overhang in the base area also plays a very important role in the project, creating a covered space with a kind of veranda feel. A special detail there is the large swing on which students can swing and wait for the bus.

A few years ago, you visited many of your earlier projects as part of an extended tour and summarised your experiences in your book ‘What happened to...’. What conclusions did you draw from this for your future work?

Marlies Rohmer: I had previously written a book in which I used the route from school to home to explore urban planning rules for vibrant city neighbourhoods, with a particular focus on children and their participation in public spaces. Now I wanted to write another book. But I didn't want it to be a classic architect's book celebrating myself; I didn't find that very exciting. Instead, after a conversation with a journalist, I had the idea of visiting 25 of my earlier works during a trip and looking at them from today's perspective. In the process, I learned a lot about how users change a building after the architect has left. And I learned a lot about materials and also saw that my brick buildings in particular have aged almost entirely with dignity.

You have been working successfully as an architect for over 40 years now. What role did having to assert yourself in a profession that is still male-dominated play for you?

Marlies Rohmer: In the beginning, I was one of the first women in the Netherlands to set up my own architectural firm without a male partner. And it was a success: a few years later, I had around 45 employees working in my office. But when I became pregnant, I tried to hide it with loose-fitting clothes until I was seven months along – for fear that people would find out that I was running the firm on my own and stop giving me work. At the same time, when I first started out on my own, I always put the title ‘Ir’ (“engineer”) in front of my name to emphasise that I had studied architecture and was not ‘just’ an interior designer. I wouldn't do that today, but times were different back then. However, women still occupy a different position in the industry. For example, I once accidentally received an email correspondence via CC in which clients were discussing whether they should invite me to a competition. There I had to read that they didn't consider me a lap cat, but that I could win the contract for them if they ‘put me on a leash’. They would never have spoken about a man in this way.

You were in your mid-20s when you started your own business straight after graduating. How do you assess the situation for young architects today?

Marlies Rohmer: Looking back, I think it has become much more difficult for the younger generation. Most of them lack the necessary references to be invited to larger competitions. In addition, the industry and training have changed considerably. In the past, architects were usually all-rounders, but younger architects have generally not learned this, so they often lack the technical and construction skills. And that's quite problematic because it means that many services have to be outsourced at great expense. As a result, the entire construction process is becoming increasingly fragmented. I am now 67 years old and have been fortunate enough to realise some great projects and am now set for life. That's why I now want to help younger firms and young architects to open doors and win contracts. On the other hand, this also benefits me greatly because I get to experience a completely different work culture each time. And my clients also appreciate it when a young firm is involved, but at the same time they have the assurance that everything will run smoothly. A good example of this is the competition for the Esserberg school campus in Haren near Groningen, which I have just won together with the young Rotterdam-based firm Shift architecture urbanism. This is a rather complex project in which we are transforming an existing primary school building from 1960 and adding new buildings. The aim is to create a new campus with an international and bilingual orientation for children and young people between the ages of 0 and 18.

Architectural practice has changed rapidly in recent years. This applies to the use of BIM as well as to the changed economic conditions and increased sustainability requirements. How do you assess the situation?

Marlies Rohmer: Generally speaking, you now need to have a great deal of knowledge to be taken seriously in all phases of a construction process. For young firms, for example, it is virtually impossible to hire expensive BIM specialists on a permanent basis. This means they have to outsource these services, but then they no longer have the expertise in-house. In addition, fees have fallen significantly since the crisis and have remained low. All of this does not make the situation any easier. Accordingly, I see myself as a coach of sorts when working with younger firms. And that brings me full circle: as a young architect, I learned a lot from more experienced colleagues after I finished my studies. Gradually, I was able to gain experience. And now I want to pass on exactly that experience.

What Happened To My Buildings (e-book)

Learning from 30 Years of Architecture with Marlies Rohmer

Authors: Hilde de Haan, Jolanda Keesom

With support from: Stimuleringsfonds Creatieve Industrie

Design: Koehorst in ‘t Veld

ISBN: 978-94-6208-334-9

Year: 2017

Language: Dutch, English

ISBN: 978-94-6208-334-9