Individuality as a trump card

Anna Moldenhauer: Prof. Piller, what fascinates you about the topic of customized mass production?

Prof. Frank T. Piller: I started looking into the topic back in 1995 – that was the time when the internet reached German users and with it the question of how digitization was going to change industrial production. One trend that was emerging at that time was mass customization. The idea is to combine the efficiency advantages of industrial production (mass production) with individualization (customization). This is achieved, on the one hand, through a reduction in the traditional added costs of individual production through digitization, and on the other through customers’ greater willingness to pay for products that fit their needs exactly. There are now numerous publications and research studies into the subject of mass customization, but even after all these years in the market the link between mass production and individual products is far from a given.

What conditions are required for manufacturers to be able to offer customized mass production?

Prof. Frank T. Piller: That is very industry specific. The production technology has certainly become more flexible in the meantime, but successful interaction with the customers for whom the product is being configured is still crucial. There are innumerable mass customization offerings that actually don’t make any sense because they offer configuration options at points for which there is no demand. That may then generate short-term attention for the novelty factor but is not of interest over the long term. One reason is that classic market research methods are designed to find out where customers are the same – in order to then put them in a segment. Whereas, by contrast, successful mass customization is about finding out where customers differ – and acknowledging a manufacturer’s ability to cater to that individuality. It sounds simple – but in practice it’s not.

Is that the only challenge for companies that want to become mass customizers?

Prof. Frank T. Piller: No, the biggest challenge for these companies, in my experience, is changing their business model. So far, there are no established mass manufacturers that have a stable mass customization offering. The successful customizers are currently more like start-ups that have grown with this business model during the course of digitization. The furniture industry, for example, is the opposite of mass customization – customers are indeed able to configure many features, but generally have then to wait months for their product to be delivered. These are anything but the stable processes on which mass customization is based.

So should manufacturers view the heterogeneity of customers as an opportunity to tap new markets and target groups?

Prof. Frank T. Piller: Yes, exactly. Mass customization is also sustainable: The products are always modular and therefore easier to repair or to expand. This reduces wastage of resources. However, the currently successful mass customization offerings are rarely related to the offering for end customers, but rather are to be located in the B2B area. And that’s not only the case for industrial goods! It also applies to retail. In other words, a manufacturer enables a local retailer to produce a custom-fit assortment for end customers in a local market. One of the biggest mass customizers worldwide is Cimpress (with brands such as Vistaprint): They have become big partly by enabling graphic designers to sell not only the design but also the finished products. Similarly, Spreadshirt from Leipzig bundles the individual offerings of many creative people in one place.

For a long time, customers were essentially unwilling to become actively involved in the design process in order to personalize products. Why has that changed?

Prof. Frank T. Piller: On the one hand, it’s classic consumer maturity – these days we order virtually everything online and configure our demand there, too. The young generation is also already accustomed to personalization as part of its use of apps and social media. This is accompanied by the expectation of being able to personalize every offering, something that is carried over into the rest of the market. Networked, i.e., “smart” products, are actually mass customization products anyway – such as programmable coffee machines that give me the choice of designing the brewing process such that the result matches my taste. As a result of this change, the demand for mass customization has increasingly reached consumers. One interesting research tool in relation to this is “The Configurator Database” from Vienna-based agency Cyledge, which has since 2007been providing a steadily growing overview of web-based configuration options in industries of all kinds. Amusingly enough, it reveals that the most profitable mass customization products are cat trees. But it makes sense: If I’m buying a pedigree cat for several thousand euros, I don’t then want an ugly scratching post in my home afterwards. A classic unsatisfied heterogeneity in the market with which money can be made.

Don’t designers run the risk that their creations will be changed beyond recognition if the customer is integrated into the value-creation process as co-designer?

Prof. Frank T. Piller: In my experience, there are many designers who see it more as a challenge to design a solution space that is always logical and aesthetically pleasing, regardless of which features the user configures. Or who want to develop new product proposals based on customer data. Practice has likewise shown how important it is not to overwhelm customers. Paradoxically, I hear time and again that the fewer configuration options a mass customizer offers, the more it sells. This is where designers are faced with exciting tasks in designing precisely the right customization options.

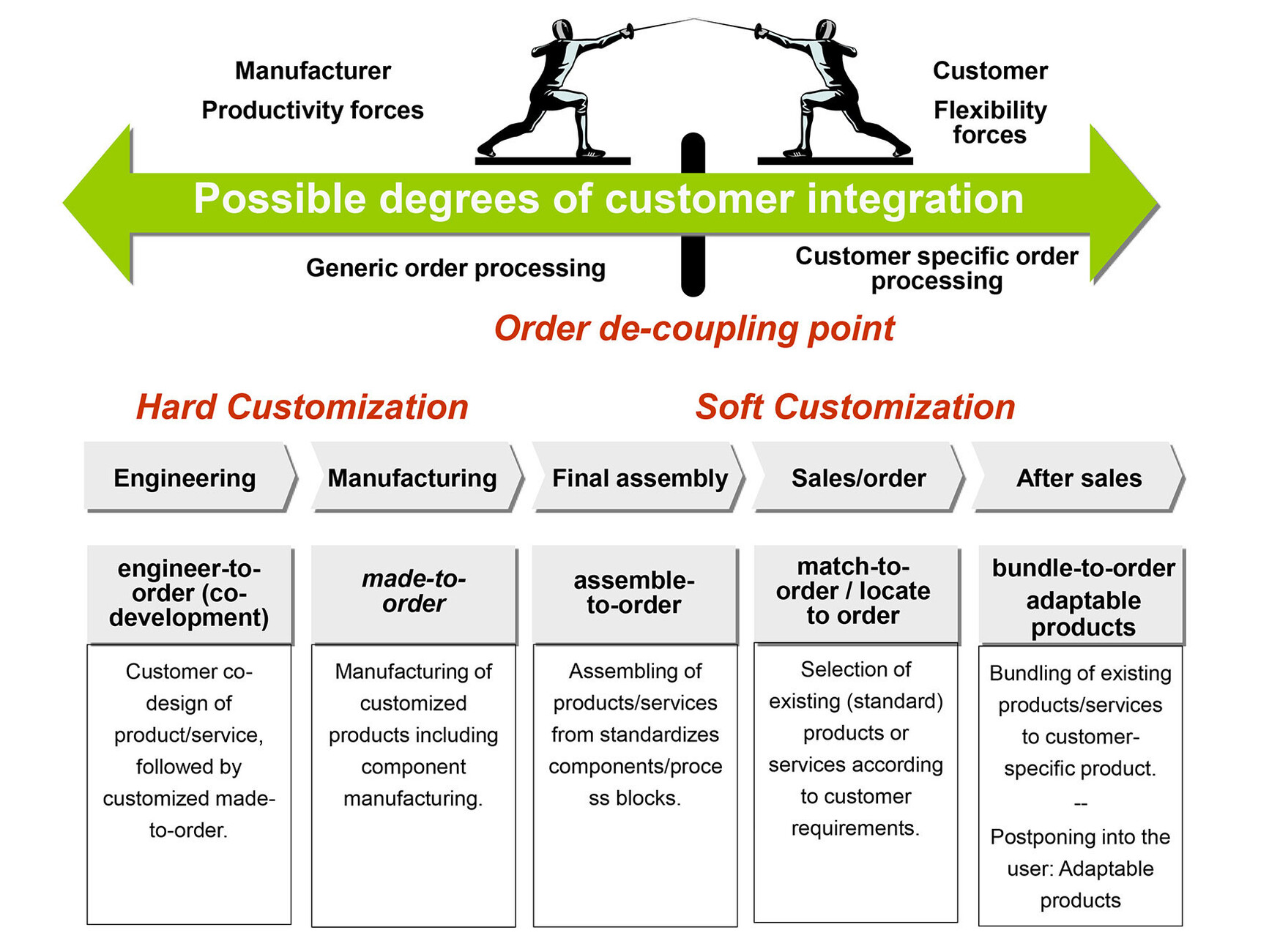

Within mass customization, there is differentiation between “soft” and “hard”. In the case of soft customization, the customer is not directly involved in the manufacturing process, so the personalization takes place only outside of the actual production. In hard customization, customer preferences have a direct influence on production of the product. Which approach would you recommend?

Prof. Frank T. Piller: Soft customization has been more commercially successful thus far, primarily in the service sector. For example, I don’t personalize the sneaker but rather the shopping experience by using a matching algorithm. I rely on a configurator to specify my wishes, but then you get “match to order” rather than “make to order”. In other words, from the range of existing products, one is selected that best matches my customer preference. Hard customization offers more possibilities but is undoubtedly more challenging. Perhaps there is an opportunity to connect the two: If, for example, I have an algorithm that analyzes the customer’s Instagram profile, then I can configure the perfect product for a person based on this data. With this digital “preference insight”, we now have powerful consumer data available to us. Lexus and 23andMe took this as a april fool to the extreme in 2018 and presented the “Genetic Select”, whereby human genetics were used for the design of a customized car. Muesli manufacturer my-muesli.de also already offers personalized DNA muesli.

Customized mass production can also reduce manufacturing costs, for example by reducing the variety of components required in the preliminary stages. In your opinion, what is the ideal way to reduce costs in mass customization?

Prof. Frank T. Piller: That depends very much on the industry. With sports shoes, for example, 3D-knitted fabric has made it possible to simplify construction of the shoe and to incorporate individual programming of the machines. Here, individualization on the production side is just as economical as mass production. The main cost driver, however, is generally not the configuration but rather the customer interaction. This should be automated as much as possible in order to reduce waiting times. There’s still a great deal of potential here.

What would you say manufacturers often do wrong in management?

Prof. Frank T. Piller: Production is frequently considered too complicated, and offerings are created that customers don’t even notice. Yet configuration does not stop at the design process because it is equally part of the sales process. Our medium-sized German companies would actually be perfect mass customization manufacturers, only their structures are unfortunately not uniform. Many areas of the company are kept separate from one another – sometimes design, sales and brand management are handled by different service providers. But that’s not necessarily a mass customization problem. Changing existing structures in the company is a major challenge in general.

In other words, for mass customization to be successful, do you need better networking within the company?

Prof. Frank T. Piller: Exactly. Companies like Ebay, Alibaba or Amazon are already investing in a comprehensive mass customization offering with factories specially designed for this. These also give designers new potential to bring products to the market on their own. Just as Amazon and co. now take care of sales and logistics, in the future they will also offer ever more production to order as a service.

Does that mean mass customization also promotes equality in the market?

Prof. Frank T. Piller: Most definitely. It is also more economically sustainable.

In preparing for this interview, I read that Western manufacturers are lagging behind when it comes to mass production of customized products. Why is that the case?

Prof. Frank T. Piller: The production and thus also the expertise has been relocated by many western manufacturers to countries in the Far East. In addition, craftsmen in our culture are considered to be individual producers. Only a few dare to offer mass production, let alone actually want to do so. Homag GmbH, one of the biggest machine manufacturers for the furniture industry, for example, developed a concept years ago named “KücheDirekt” for a mini kitchen factory to be operated by craftsmen. As in a franchise system, many processes were to be computerized, while the measuring, production and assembly were to be done primarily by trained hands. With this offering, it would have been possible to produce a complete individual kitchen, including installation, within one day, with affordable costs. Yet the offering was unsuccessful because there was no market for it. For the existing kitchen industry, it was an unwelcome competitor and for the craftsmen it did not fit with their self-image, since they do not see themselves as industrial producers or sellers. So there’s a mindset problem.

Can you name a manufacturer that already offers mass customization successfully as standard?

Prof. Frank T. Piller: Dutch tile manufacturer Mosa has successfully taken up the challenge with its products. Mosa is industrial in nature but still offers an extensive range of configuration options.

Will mass customization completely replace classic mass production in the long term or will both offers exist in parallel in future?

Prof. Frank T. Piller: I believe the systems will exist parallel to each other. This would in itself require radical change here, particularly in relation to sustainability. Currently, mass production still involves too much wastage of resources. Only if production becomes more local across the board and we consume less and more conscientiously can mass customization replace mass production over the long term.

What are you currently researching in this field?

Prof. Frank T. Piller: My current research is in the area of smart products and how these can be used for mass customization. The configurators here are already integrated into the product, which raises many questions, such as the dictatorship of the algorithm – how much freedom does the person need for individual selection if the algorithm actually knows much better what I want? It is also interesting to analyze the capabilities required in the management of an established company to achieve lasting change in the existing business model in the direction of mass customization.

What is lacking in manufacturers’ understanding of mass customization?

Prof. Frank T. Piller: It always amazes me that mass customization is defined with the offering of a product in various colors or an individual print. An aesthetic surface is merely the start of the options – functionality or fit are far more value-generating individualization options.

It sounds as if you still have a lot of work to do in communicating the possibilities.

Prof. Frank T. Piller: I’m pleased to hear that. I’ve been studying this topic for more than 20 years now, but perhaps only today is the market ripe for the opportunities arising for manufacturers and consumers.