The Munich Complex

Its calm, inner beauty is the first thing you notice about this book. Indeed, at first glance, “From the Room to the City. Munich. Urbanity and Complexity” does not make a particularly eye-catching impression, in fact, quite the reverse is true. With its thick gray cloth binding and its engraved serif font, the book appears to be aiming very much at understatement. However, it sits well in the reader’s hands and is light enough, slightly smaller than A4 in size, and while rather fat, it is, however, not a hefty tome. Nor were the three titles on the cover able to agree about their font sizes, and thus to decide which of them is the title itself and what merely the subheadings. It was almost as if the readers were allowed to decide that for themselves.

However, when the reader does finally open the book, it reveals itself in all its bright airiness and effortless expertise. This is evidenced firstly in the wonderful illustrations by Munich-based photographer Simon Burko that factor in a generous amount of white space as surrounds and stretch out over the relevant pages, seldom more than one or two per double page. These photos are classic cityscapes and are reminiscent of the work of Thomas Struth – the sky a smooth, regular, almost white world with buildings standing out on it, most of these apparently taken in the early hours of the morning. Here, people are in evidence only infrequently; sometimes morning mist still drifts past the fronts of the buildings. It is only when the photographer heads for those bustling places such as the Olympic Park, the meadows either side of the River Isar, or the Englischer Garten that the photos become broad, animated panoramas rather like the picture puzzles of an Ali Mitgutsch, the kind over which our eyes can roam seemingly endlessly.

Even so, in Burko’s photos we sometimes come across the kind of settings that are familiar even to those readers who are not Munich residents. We might spot the spire of the Frauenkirche, the empty Theresienwiese, a wide expanse of barrenness, Haus der Kunst, Königsplatz, the Alte Pinakothek. There is no shortage of well-known places. However, the vast majority of Burko’s photos lead us with a sense of tranquility to those everyday places in the city, to those interchangeable locations that go to make up the special character of the city that is Munich. It is only seldom and sparingly that items are labeled. Only on occasion is sparse information about various buildings, architects, construction periods and sometimes even their dimensions provided at the upper edge of the picture. In some of these text blocks readers come across short sentences, observations rather than explanations, something akin to personal travel journals or the comments written on postcards: “In Döllgast’s map of the city, the blocks are arranged in a rigid pattern, but there are repeated changes on a small scale, resulting in a large number of different urban settings.” Or: “The entrance to the Hofgarten through an aperture in a wall masks the Residenz’s vast size.” And: “The ornamental hole in the middle of the bridge reduces its weight and makes it more resistant to flooding.”

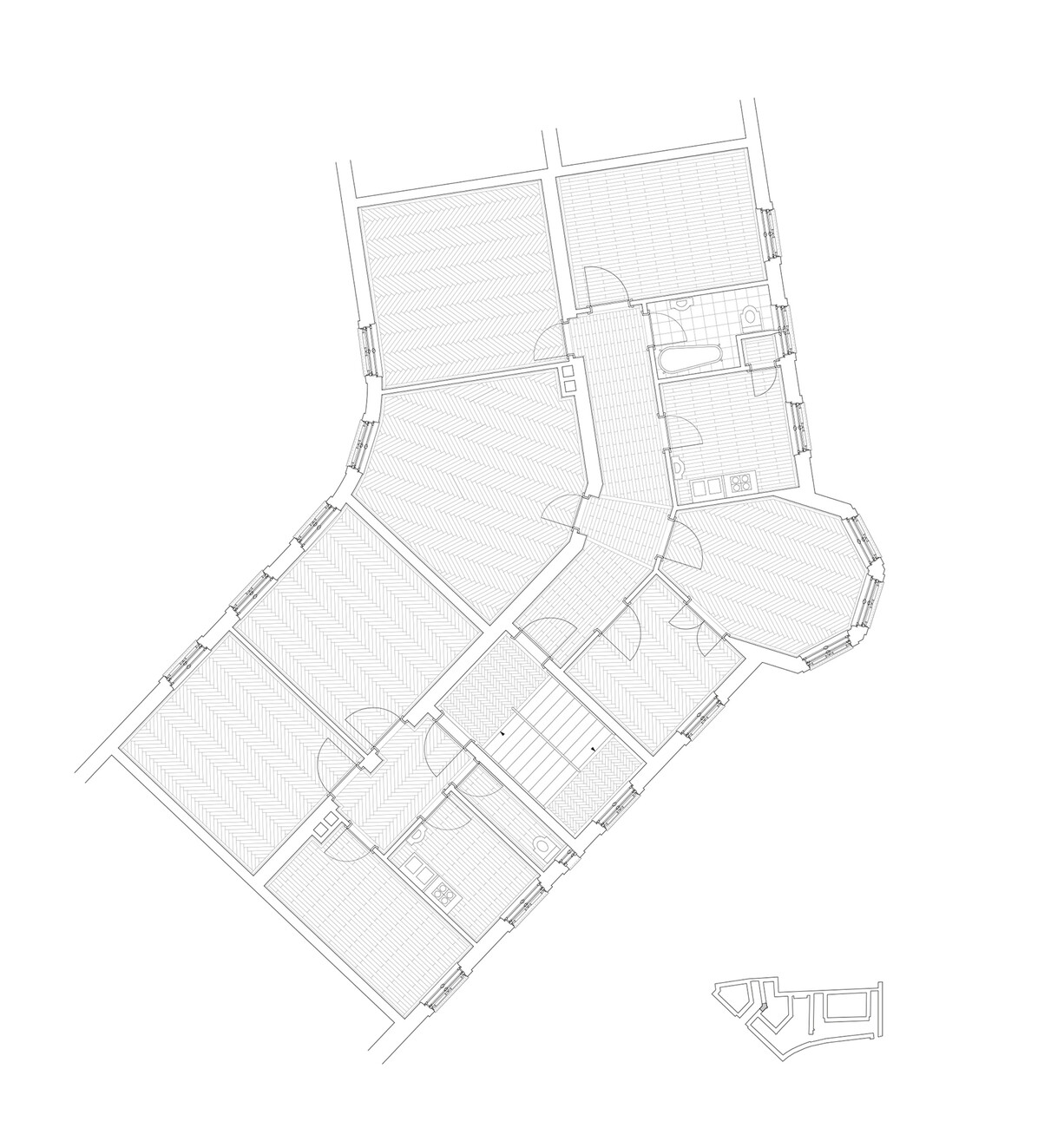

The images are loosely arranged into five chapters with names such as “Big Form”, “Fragments”, “Dreams” and “Re-use[JG1] ”. Between these there are not only short texts addressed like letters from Bates to Krucker or vice versa, but also and more importantly sketches spread out like the photos individually and generously over the white space on the pages of the book: Floor plans, as-built plans, sectional views. Some of these are large layout plans on a scale of 1:5,000, others imitate a detailed residential floor plan. Along with the photos, it is these sketches that make this book so special. They were realized in collaboration with the students and repeatedly focus on different districts of the city that were reconnoitered and then analyzed in minute detail. This has allowed the team to produce a meticulously researched layout of the city covering a major portion of Munich’s entire downtown. Sections of this are reproduced here on repeated occasions. This lends the photos a third dimension and provides them with spatial contextualization of the kind that I have seldom come across in a book. At some point, it is as if readers had stepped through a door in the photo out into the city, after which they are indeed able to see what is located behind the wall to their left and right, what sequences of rooms follow one another, instead of, as is usual in photography, their perception being stuck in one particular section of the picture.

With this in mind, the volume under consideration has indeed turned out to be a cheery book with a third dimension that shows Munich to us in the kind of light that we have never experienced before. And the book still has any number of tips to offer us for our next trip, ideas about what is worth taking a look at – the Borstei, for example, Wolffs Block, the old Nordfriedhof (Northern Cemetery) or, for anybody up for a really tough challenge, the stormwater basin under the city – however they manage to reach it. The photos and ideas discussed in this book will, at any rate, help us to take a fresh look at Munich’s downtown in future and to be more rigorous about the way we look at it.

From the Room to the City

Publisher: Bruno Krucker und Stephen Bates

German and English

352 pages

Park Books publishers

ISBN 978-3-03860-288-0

49 Euro