The City's Agents

Andrea Eschbach: On your website, you describe yourselves as ‘agents in the city’. What do you mean by that?

Shadi Rahbaran: We understand it to refer to a sense of responsibility: we should be aware of what we are building and the impact architecture has on urban society. When we founded our office over ten years ago, this concept felt right to us. It has evolved over time, but fundamentally it's about thinking ahead with every project: Who are we building with? What does that mean for the location? What specific quality can we add?

Ursula Hürzeler: As agents, we want to do more than just map out a competition programme. These often only contain the uses, the specific requirements for the building. But we are interested in what additional social opportunities can be created – such as communal spaces or places for different groups of users. This is rarely requested, but it is central to the quality of a project.

Shadi Rahbaran: Wir versuchen in frühen Phasen möglichst offen zu denken und verschiedene Optionen auszuloten. Der Ort spielt in dieser Phase eine zentrale Rolle. Durch diese Offenheit entstehen oft kleine Entdeckungen, die dann das ganze Projekt tragen. Wenn wir uns in einer frühen Phase unsicher sind, wie wir ansetzen sollen, hilft es fast immer, uns den Kontext sehr genau anzusehen – die Menschen, die Umgebung, die Geschichte.

You founded your office in 2013. There are not many young female architects who set up their own practice. How did you get to where you are today?

Ursula Hürzeler: I had always wanted my own office, but it took a while for the right circumstances to come together. And it's true that many milestones in life occur during the same period: between the ages of 30 and 40. That's when you decide to set up your own office – and at the same time, you're thinking about starting a family. The job is very intense. The industry is also very competitive and still male-dominated. It takes a lot of energy and time to assert yourself in this environment. And our industry continues to be characterised by working conditions that are difficult to reconcile with the desire for a better work-life balance.

Shadi Rahbaran: On top of that, the structural problems remain. There is enormous pressure in the industry: clients demand a lot, sustainability is required, everything has to be done quickly and perfectly at the same time. In addition, there is still a feeling that men work ‘more reliably’ or ‘faster’ – an outdated but persistent narrative.

Ursula Hürzeler: Role models are important. Many project processes are more complex today, but at the same time there are too few visible examples of female architects or mixed teams. That is changing, but slowly.

Your portfolio is incredibly diverse – ranging from experimental and public institutional projects to urban strategies, spatial installations and exhibition scenography. What connects all these projects?

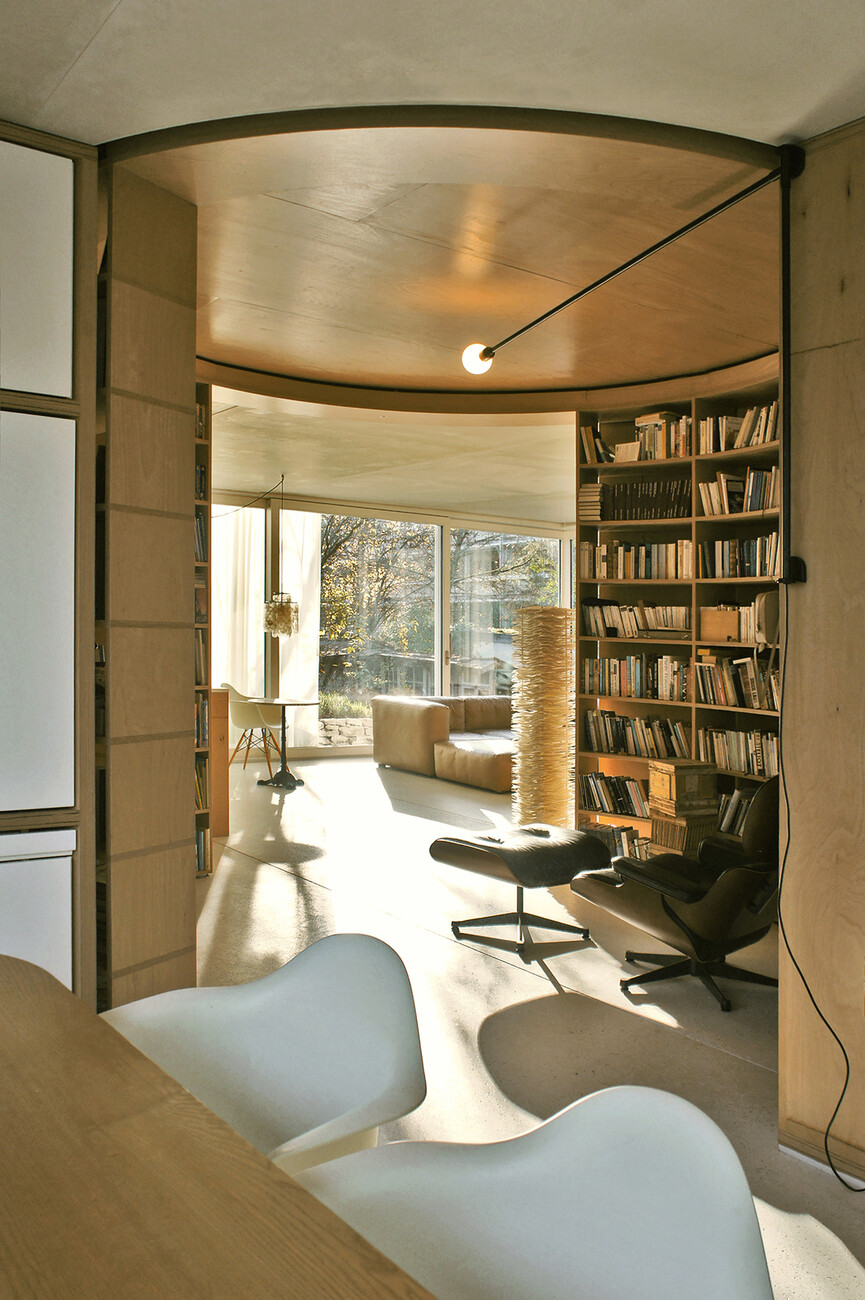

Shadi Rahbaran: The spatial scenography is very important to us – whether it's enfilades, cross-views or emphasising diagonals. We have a lot of fun inventing new solutions, doing things differently than anticipated.

Ursula Hürzeler: Design often revolves around movement within a space and the relationships between spaces – internal permeability, transitions between inside and outside, proportions, lighting, materials. For us, architecture is always connected to people: how do they perceive spaces? How do they feel in them? This is not purely a conceptual exercise – ultimately, the space has to function.

Your team seems to play a big part in this.

Shadi Rahbaran: Yes, we work intensively as a team and have employees from many countries with different educational backgrounds. This diversity is valuable and strengthens the vision of the office.

Ursula Hürzeler: We like to challenge ourselves and the team. This prevents us from simply repeating what has worked before. Different perspectives generate new approaches. That motivates us greatly.

Social conditions have changed over the last ten years. To what extent does this affect architecture?

Ursula Hürzeler: Very strongly. Not only in terms of sustainability or climate issues, but also socially. Users' needs have changed, but spaces often lag behind. Many programmes do not reflect social realities – such as communal spaces, flexible uses or places that enable different lifestyles.

Shadi Rahbaran: Topics such as inventory, densification, reduction and transformation play an important role for us. When we design, we always try to take them into account.

Reduction was already a priority for your ‘Movable House’ in 2018.

Ursula Hürzeler: Exactly. The ‘Movable House’ is an experiment, a house in motion. The residential building, which was designed for a family, uses a minimal amount of space and materials. It can be constructed, dismantled and reused in a very short time.

Shadi Rahbaran: It is a house without a location. It was not designed for a specific site, but is intended to be implemented in various locations on a temporary basis. The aim of the pilot project was to explore the limits of statics and building physics and to use new combinations of materials.

Has the house from its backyard in Riehen, Switzerland, already moved out?

Ursula Hürzeler: No, not yet. At the moment, the family with their two children feels very comfortable in the house. But it is in the nature of things that the needs of the residents will change. We wanted to take this into account and designed the building to be flexible.

‘Keeping what's good’ is one of your principles. What exactly does that mean?

Ursula Hürzeler: When working with existing buildings, we strive to find solutions that work with, rather than against, the existing structure.

Such as in the renovation and extension of the Hebel School in Riehen, where you won the competition in 2023.

Shadi Rahbaran: Indeed, in our competition entry, the 12 existing classrooms are expanded by a further 12, while the listed part of the school building is retained and the Hebelmatte is largely kept free. It was important to us to preserve this green outdoor space. A new building would have destroyed this space. Instead, we added extra storeys and extensions. This was structurally challenging, but possible with the help of good engineers. The jury found this approach convincing, and it was also central to the neighbourhood. This shows once again that competitions should be open-ended so that alternative solutions can be considered.

Another theme in your work is density. The Colmi project, for example, also dealt with densification. Here, a dense urban ensemble of residential, small commercial and studio spaces was created in a backyard in Basel.

Ursula Hürzeler: The new living and working spaces were arranged along the existing courtyard walls and designed both as conversions of the existing structures and as complementary new buildings. The communal courtyard forms the spatial and social centre of the project, which is equally available to all tenants and serves as a meeting place. We made maximum use of the area without building over the courtyard garden; on the contrary, we opened it up. Our goal was to create a place for people to come together. We succeeded in this, and there is now even a group chat for the residents.

How much density is sufficient?

Ursula Hürzeler: We really like the expression ‘Dichtelust’ (literally ‘desire for density’), which comes from an exhibition at the SAM Swiss Architecture Museum in Basel. Density often has negative connotations in Switzerland. Yet there are numerous examples of sensible urban densification that promote the attractiveness of urban living.

Shadi Rahbaran: Density can work very well if the quality is right. Good communal spaces are crucial. However, the amount of living space per person is constantly increasing, which exacerbates the housing shortage. Smaller flats with high-quality shared spaces would be more attractive to many than large units, which are often unaffordable.

Ursula Hürzeler: Viele Menschen – Singles, ältere Menschen – bräuchten kleinere, gut gestaltete Wohnungen plus gemeinschaftliche Räume. Aber der Markt produziert nach wie vor Standardgrundrisse. Die Realität hinkt den Bedürfnissen hinterher.

Shadi Rahbaran: With the ‘Movable House’, we built an extension for the residents in the backyard of the parents’ house – a kind of ‘Stöckli’ for the young people. It is a project that shows how additional living space can be created in a limited area without requiring significant resources. Such small, selective densification projects could have a big impact in many neighbourhoods.

Since summer 2025, you have been jointly heading the Institute of Architecture at the University of Applied Sciences and Arts of Southern Switzerland in Basel. Previously, you taught design and construction there as a duo. How does working with students influence your own practice?

Ursula Hürzeler: Dialogue with students is extremely important. They bring energy and curiosity, are driven by the desire to make a difference – and they are not yet showing any signs of fatigue. We learn a lot together – about new materials, sustainable construction methods, new ways of living, the joy of experimentation. The university offers a good counterpoint to the often sluggish construction industry. There, you can see where architecture could be heading.

Shadi Rahbaran: Interestingly, educational institutions are advancing much more rapidly towards the future than the industry itself.

What is the teaching about?

Shadi Rahbaran: We have developed a three-year series of themes. This year's theme is ‘Transformation’, next year's theme is ‘Staying Cool’, which deals with climate change and how to learn from the past and view buildings as part of ecological cycles. The university should be a shared laboratory, from the first year of study to the master's degree.

Let's return to practical terms: you are currently focusing on large-scale transformation with the development of a former industrial site in Sachseln.

Ursula Hürzeler: Even in larger projects – such as the current one in Sursee – we try to respect and emphasise existing qualities. We are working there with an idea from two areas: a dense ‘Werkgasse’ at the front and an open ‘garden city’ behind it. This spatial charging creates character. In Sachseln, it's about real transformation: continuing to use existing substance, preserving identity and at the same time enabling new forms of living and working.

What makes transformation projects interesting for you?

Shadi Rahbaran: They are complex, but manageable. You can intervene in a targeted manner without destroying identity.

So it always comes down to the interplay between space, social context and users?

Ursula Hürzeler: Yes. Architecture is created through long, complex processes involving many different parties: teams, specialist planners, building contractors and authorities. It requires dialogue and perseverance – but this is the only way to maintain design quality while remaining feasible.